This is written with great sadness at the very dining room table in Shropshire where my dear old friend, the brilliant raconteur, would-be politician and City financier Patrick Paines would so often be the very last person left sitting, often until 3am.

Patrick was an usher at my 2003 wedding, and regular house guest for twenty years. He is the first of my truly close friends to die – stoically on November 8th at the age of 53 from a fast spreading cancer.

So I’m writing this ‘The Patrick I Knew’ obit with a tragic sense of resigned irony in the fact that a man with 1950’s matinee idol looks who was so popular and loved – a star of his Cambridge generation and the post Big Bang City – will be denied the chance, due to a second lockdown, for his many friends to say a proper graveside goodbye.

He was dubbed ‘The Minister’ due to his command over any room when he was on form. As any visitor to his London mews house downstairs loo will have noticed, Patrick was also ‘Commander Paines’ after being promoted to Clr, Lt in the Royal Naval Reserve. One of his favourite dinner party stories included an account of how he participated in a daring Bond-like rescue mission in a ‘plastic hulled minesweeper’ during the Piper Alpha oil rig explosion of July 6th 1988 whilst serving in his last summer vacation at Cambridge.

Whilst his college contemporaries were on work experience for American banks, or inter-railing around Greece, Patrick was involved in a dawn mission to navigate his way through fifty foot flames in the North Sea to pick up floating oil rig workers, dead and alive. He would relate how 167 were killed in the rig disaster, including two crew of another rescue boat in the inferno-like waters.

‘When we were ordered to pull out, due to the black flames, thirty bodies were still not recovered. Our hull was melting in the heat’ he’d say as he lit up again and refilled his glass. Various attractive girls hung on his every word.

The inspiration for his ‘less fizzy’ Indian beer came from boozy dinners in Cambridge curry houses at which Patrick was principal ‘tastemeister’.

One of his closest Cambridge friends was hedgie Jonathan Bailey who now works as a fund manager in California. ‘Patrick was kind, loyal, quick witted and an eloquent speaker. This may explain why he was a regular choice as best man, even to people he hardly knew’.

After graduating from Cambridge in 1989, Patrick worked until 1997 in corporate finance at blue-chip stockbroker Cazenove, followed by stints at NatWest Markets (Africa and mining), Societe General Securities and Cannacord. He also became an investment banking partner at Lakeshore Capital LLP and a partner at Javelin Capital LLP .

As related in Bottled for Business Karan (now Lord) Bilimoria’s 2007 book about the entrepreneurial story behind Cobra Beer, Patrick was also a key founding director and shareholder of Cobra, which started in the late 1980s with just £30,000 of funds. Bilimoria is now President of the Confederation of British Industry. The inspiration for his ‘less fizzy’ Indian beer came from boozy dinners in Cambridge curry houses at which Patrick was principal ‘tastemeister’. As a director, he helped raise the capital and turn Cobra into a global ‘less fizzy’ Indian beer business, now served around the world.

His early death reminds me of how many of my Bonfire of the Vanities banker friends became another Lost Generation. They didn’t die of being blown up in the trenches but their talents and careers often burnt out or shattered in different ways. Many simply embarked on banking careers that – as graduates of History or English Literature – they simply weren’t suited to while others fell victim to unprecedented technological and regulatory change. The world found it didn’t need highly paid fifty year olds in striped suits selling stocks anymore.

Patrick was such a case. As Michael Lewis put it in Liar’s Poker, which became a graduate training manual for my contemporaries, he did not regard banking as ‘work’, rather it was ‘more as if I were going to collect lottery winnings’.

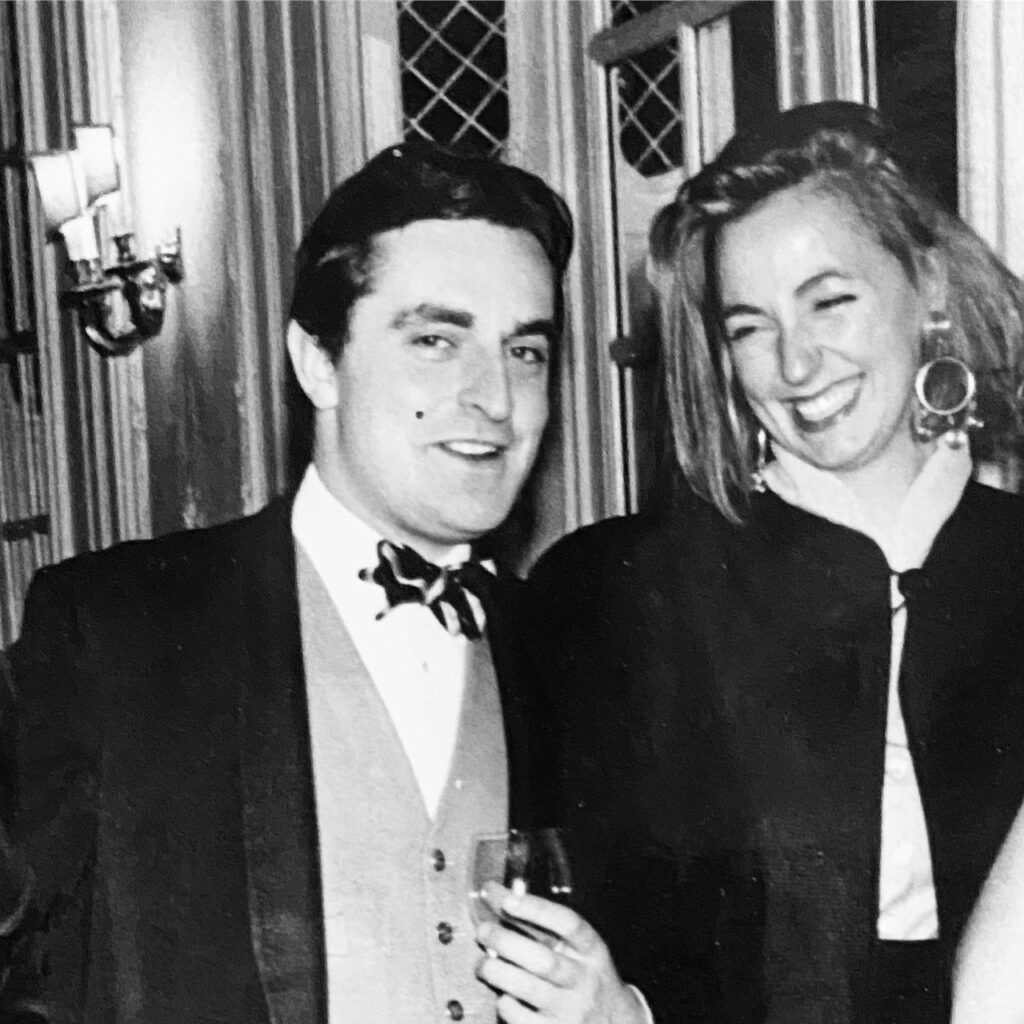

Patrick holding court at a Mayfair wedding in 2003

Patrick was a fully paid up member of this generation – although banking was almost certainly the wrong career choice for him. The City was only a means to his true ambition: a career in politics. He could have been a brilliant lawyer, QC, historian, Bishop, or Ambassador – although I suspect he may have ended up as the sort of popular Honorary Consul in the Caribbean who lives for his first G&T before lunch.

When abroad – work or holiday – he dressed in a linen jacket, polished brogues and Pitt club tie like a character in a Somerset Maugham novel. His adventures were often the stuff of a novella. His friend Simon Gray remembers a sticky moment when they found themselves, on a mining exploration business trip – with a chauffeur driven black Mercedes outside – drinking Johnny Walker Black label in a downtown bar in Coast Cape on the African Gold Coast. When they were presented with an outlandish bill around 3am, the situation became ‘prickly’ when they contested the accounting.

‘Heavies surrounded us and it turned ugly’ recalls Simon. ‘The situation was only diffused when Patrick claimed that he was the country’s new High Commissioner, and they somehow believed him. We ended up leaving on excellent terms at 9am’.

Patrick had an irrational dislike of ‘pogonophiles’ (beard lovers).

One of his secret weapons was that Patrick always saw the best in people. He had a laser like way to identify it in others, although wasn’t always so good at seeing the very best in himself. He enjoyed lampooning social tribes – especially virtue signallers – in the letters pages of newspapers. A classic was his letter of 13th January 2005 to the Daily Telegraph in which he delighted in the fact that a Virgin rail worker lost his case for unfair dismissal when he refused to shave his beard off. Patrick had an irrational dislike of ‘pogonophiles’ (beard lovers). He called for Richard Branson to ‘follow suit’ and remove his own.

Such Alan Partridge-style anti-PC ranting was largely a pose, or a masque. Behind it was an empathetic, self-effacing, highly intelligent and generous man who belonged in a Simon Raven or Cyril Connolly novel. Historian Andrew Roberts, an old friend from Cambridge days, recalls: ‘There wasn’t a social occasion that Patrick didn’t enhance by his sheer presence. One always knew that he would say something funny or outrageous or thought-provoking, and never anything banal. As well as a delightful human being, we have lost a truly talented conversationalist, and someone those who were lucky enough to know him will miss forever.’

If our lives are like novels, with recurring characters that drop in and out, then Patrick belonged in the Evelyn Waugh world of Black Mischief and The Sword of Honour trilogy. He reminded me of Waugh’s brilliant but flawed Oxford friend Brian Howard who was a recurring composite ‘condemned playground’ character.

Howard, who died aged 52 of excess and unfulfilled promise, living with his mother, was famous for his outrageous one liners which included: ‘Anybody over the age of thirty seen on a bus has been a failure in life’. Alas, it was a perfect example of wit also serving as autobiography.

Patrick was brought up in Piltdown, East Sussex, the son of a solicitor who had served in the Royal Navy. Whether being raised in an English village best known for the most notorious archaeological whopper of the 20th century (the fossilized bones of ‘Piltdown Man’ claimed to provide the missing biological link between ape and man) had fuelled his imagination is unknown.

Ever since Patrick worked as an intern in his gap year for his local MP, Sir Geoffrey Johnson-Smith MP, the charismatic broadcaster and war hero, Patrick wanted to enter Parliament. To be a Tory MP in his thirties and then a Privy Councillor and Cabinet member. His greatest ambition was to be Chancellor in the style of Nigel Lawson whom he much admired. The banking world was largely regarded as a means to an end: primarily a lunching pad to make enough money by forty to focus only on his political career.

Varsity described him as ‘everything vile and repugnant in old guard conservatism’

His C.V. began promisingly. He was (reportedly) head of school at King’s Canterbury in his final term (7th term Cambridge entrance) with the Cantuarian magazine reporting on his fondness for wearing a dashing silk cravat and making ‘stirring speeches’ at school debates. He had a first class intellect (of which more later), but only got a 2:1 in history at Peterhouse Cambridge due to other Hon Sec distractions. One essay for the Part I general paper came back with the comment “wild, woolly and hopelessly anachronistic” but then it had been written late at night over a second bottle of Pitt Club port.

When Varsity described him as ‘everything vile and repugnant in old guard conservatism’ he took it as a compliment and had it framed. On once occasion he was fined £5 for emptying a fire extinguisher on a porter when he tried to curtail a late night ‘disco party’ in his rooms following a Beefsteak Club dinner.

Despite such Vile Bodies-style antics,he will be remembered for his charisma, kindness and empathy. Although he never married (his heart was broken at Cambridge), women (including Joanna Lumley) adored him as a friend as he made them laugh. As Sarah Tyser, wife of his Cazenove colleague Harry Tyser, put it: ‘I remember how he could pierce pomposity with the merest hint of a raised eyebrow’.

The story of his first thirty five years can, indeed, be told by the framed photographs, honours and medals (including the Reserve Decoration of the Royal Navy) certificates that decorated the above-mentioned London mews house loo: President of the Beefsteak Club (a Cambridge equivalent of the Bullingdon), Hon. Sec. of the University Pitt Club (a louche, politically incorrect Cambridge gents only club with its own premises in Jesus Lane and generous credit facilities). Hon. Sec. of The Grafton Club, which was a Peterhouse-based champagne breakfast club (long since banned) at which guests were required to wear morning dress.

The Grafton – attended by dons and chaplains alike – was straight out of Tom Sharpe’s Porterhouse Blue and started with a four course cooked breakfast, followed by champagne all day, often ending in search of a London party. I recall one breakfast where a Cambridge double-decker bus parked outside the college was nearly commandeered (Patrick never drove) and then leading guests into a London drinks with red plastic traffic cones on their heads.

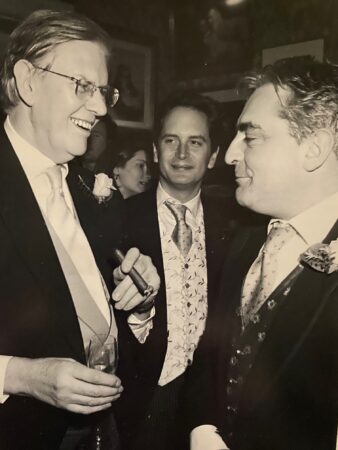

Patrick and Sir Bill Cash MP and Cazenove friend Hugh Warrender

Most memorably, Patrick was chairman of the Cambridge University Conservative Association in the Michaelmas term of 1988 (his members included Nick Clegg). Patrick used the Pitt’s oak panelled upstairs private dining room to lavishly entertain political figures and Cabinet ministers (including Jeffrey Archer, Sir Geoffrey Howe, Ken Clarke), and editors like Charles Moore of The Spectator, plying them with club claret and plotting with them his own would-be Westminster political career.

CUCA flourished under his charismatic chairmanship during Margaret Thatcher’s second term. Under Paines, Cambridge became the only British university to have a Conservative president of the Student Union, something that would be impossible today. On two occasions, he had to smuggle his high-profile speakers – including the Bishop of Chichester – into the meeting with a police escort to avoid rowdy student protestors.

Alas Patrick’s political career never went much further than standing for a council seat. It was never clear if he was officially on the Central Office Candidates’ List. Yet, bizarrely, he would report to senior Tory political figures , ‘in confidence’, that he was ‘down to the last three’ on a constituency shortlist when a by-election or new seat came up. Ultimately his multifaceted brilliance began to burn out and give way to self-disappointment.

He had a talent for self-sabotage. When Société Générale moved to new offices at Exchange House they asked employees, by email – with which Patrick always struggled – for suggested names for the new meeting rooms. He volunteered ‘The Petain Suite’, ‘The Vichy Room’ and ‘The Collaboration Board Room’ and then managed to hit ‘Reply All’ and sent this email to the bank worldwide. He left shortly afterwards.

Every generation has its shooting stars whose careers sometimes burn out too early – alas too often before their full promise and talents are fulfilled. One old Cazenove days friend, Tom Henderson, recalls that Patrick (who knew little of monetary theory or accounting) was the star of his intake as he had a genius and flair for giving senior partners and clients a highly informed and persuasively articulate analysis of any company annual report on just the lightest skimming of the document. Of course this was before Google fact check. Another Cazenove friend, Hugh Warrender, said he was nicknamed ‘The Minister’ after arriving on holiday in Spain with a group he didn’t know and ‘immediately held everybody’s attention’ due to his presence, wit and ‘bearing’.

‘He was always kind and very charming with anyone you introduced him to, especially mothers. He came to stay on a number of occasions with me in Scotland, which generally involved a lot of booze and a bit of shooting, although he wasn’t the best of shots’. He recalled a summer visit when it was terribly hot. ‘Everyone else came out in their shorts and tee-shirts, whilst Patrick remained dressed in his Viyella shirt and thick cords, sporting his brown brogues but without socks, as a concession to the warm weather’.

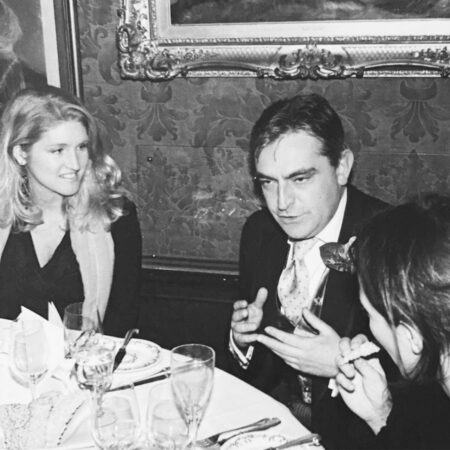

Last Man Standing at a dinner party around 2005

Patrick was ‘frighteningly bright’, he added, but possessed great humility at the same time and always willing to talk to anyone with interest. Alas, other than his Cambridge Great Love, Natalie Da Gama Rose, who became a lawyer, romantic happiness largely eluded Patrick. Camilla Grey Muir, former wife of historian Andrew Roberts and a close friend from Cambridge days recalls: ‘I have never come across anyone else who could talk so animatedly late into the night with his eyes half shut’.

She gives a typical example of the Patrick charm. At the end of a long summer of twenty-firsts in the early 1990s, they were staying in the same house party. As they travelled by car with the rest of the house party to the 21st party, he proposed a gameto be played that evening. Victory would go to the person who managed to say the rudest thing to a third party in such a way that the third party had no idea they had just been insulted.

Last Man Standing could have been his epigraph.

Needless to say, Patrick won. As Camilla recalls: ‘He commented to a particularly overweight lady at the party that he liked her dress and that he had recently attended a party where the marquee had been lined in a similar print. He spoke with such warmth and a twinkle that the large lady took his comment as a compliment’. Some years after leaving Cambridge, Mackintosh recalls Patrick inviting back for various May Balls. ‘We predictably always ended up in the Survivor’s Photo and the female who he had had his sights set on had slipped through his fingers yet again’.

Last man standing could have been his epigraph. When he came to stay at my family Shropshire home of Upton Cressett, and was still holding court at 3am, he was invariably surrounded by around half the table (who hadn’t gone to bed) including a beautiful girl, or two, laughing uncontrollably at his increasingly outlandish and risqué stories as the bottles – of rapidly diminishing quality – continued to be opened.

He was the only guest I knew whose stories were so outrageous and funny – and often fantastical – that any hope of my mother quietly ushering the dinner guests through to the drawing room for coffee proved futile. When he stayed, my mother became resigned to being greeted by a Somme of ‘swept glasses’, many doubling up as ashtrays, after Patrick had once again been the life and soul of the dinner.

On one occasion, we were a little alarmed when he didn’t surface for breakfast, and could not be found in his bedroom, or anybody else’s for that matter. Then we had a call from a neighbour who reported that Patrick was ‘asleep in our car’ and asked what they should do. When we rescued him, and asked what he was doing there, he said: ‘I wanted to get some cigarettes for the girls. But then I forgot that I don’t know how to drive’.

If have learnt anything from the shocking news of his death it is that there are such things as male muses as well as female around the Castilian Font. His wit and charm was infectious and led to love. When we look back it’s so often those with the most unique characters and talent that end up as a DNFs – Did Not Finish – in the Grand Prix of life rather than those who play by the book and then pant and wheeze across the line in later life. We think Talent Burnout is unique to artists, druggy aristos/pop stars and alcoholic writers. But their demons are the same enemies of promise that afflict the most talented, kind and original in all walks of life.

He was one of the most brilliant, amusing and unique friends of my generation. A commanding officer in so many ways, regardless of whether we were always told the whole truth.