Marvin Gaye was not a political artist until he produced one of the most influential and affecting didactic albums ever made. He stopped being a political artist soon later.

The Motown icon and “prince of soul” became a household name on the back of his velvety voice, swoon-inducing lyrics and trademark appearance. For the first decade of his career in music, Gaye would only be seen in a crisp dark suit, all the buttons on his shirt done up. Sometimes, a tie. Always clean-shaven.

That scrupulously digestible image was a masterwork of good marketing by a record company which had turned hair and make- up into an art form. Founder and ex-factory worker Berry Gordy ran Motown like an assembly line, with songwriters, sound engineers and performers kept separate in order to protect “the Motown sound”. Gordy was only 29 years old when Gaye arrived in Detroit, already something of a mogul, and an unpredictable but dogmatically ambitious record producer who had no time for quirk or, God forbid, protest. Gaye was okay with that. His childhood had forced him to be.

Marvin Gay Sr and Alberta Cooper raised their four children in a Washington, DC slum made up mostly of African Americans and Eastern European immigrants. Marvin Jr, the second oldest, was born in 1939. Few of the homes in Southwest Washington’s vast and overcrowded public housing projects had electricity or running water. It was not much different when Al Jolson lived there as a boy in the 1890s.

Gaye’s mother worked as a cleaner in the plush homes of political and financial elites in the capital suburbs. Marvin Sr, a preacher who converted the family home to his church, didn’t earn a regular wage. But he controlled the goings-on and compensated for his economic dependence by beating the children nightly, usually with his belt. Marvin Sr also bossed the family around during his living room services, which he often delivered in a dress. This confused the children, particularly his sons. On the one hand, their father was a controlling, hyper-masculine presence and, on the other, appeared conflicted about his identity, perhaps even his sexuality. Gaye would later refer to his father as “a peculiar kind of cruel king”.

Gordy was less volatile, but held a similar regal status. And in the same way Marvin rebelled against his father’s domination at home by outshining the preacher with his angelic voice, Gaye had a way of getting back at – and closer to – the king of Motown. Gaye married Gordy’s older sister Anne, who was 17 years his senior. Although by most accounts an unhappy marriage, this gave Gaye automatic privileges not enjoyed by his colleagues at Hitsville. No longer a prince among kings, Marvin Jr married into music royalty and behaved as such. His competitive edge emerged: he referred to the boy genius and Motown rival Little Stevie Wonder as “that blind little sucker”, and pushed ahead of other performers for the attention of the best engineers and recording spots.

For a time, it paid off. Hit followed hit and, with his wildly successful cover of Gladys Knight & the Pips’ “I Heard It Through the Grapevine”, Gaye had the best-selling single in Motown history.

Yet the key to his success during his Motown heyday was surely Tammi Terrell, Gaye’s formidable singing partner throughout his most productive years. A Philly girl with an abundance of natural sass, Terrell contrasted Gaye’s inbuilt anxiety. Most importantly, her easy sense of rhythm made up for his awkward attempts at dancing. Gaye had collaborated with Motown’s finest, to some success, but it was the arrival of Terrell which sparked his creative passions. Their iconic duet, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, is one of the most beloved in music.

So when she collapsed into his arms on stage in October 1967, Gaye was gravely concerned. A few days later she was diagnosed with a brain tumour. Terrell had surgery and sang on two more of Gaye’s most popular songs, “You’re All I Need to Get By” and “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing”. But her illness worsened and by early 1970 she was blind and wheelchair-bound. She died that March, aged 24.

Gaye fell into a deep depression. Though he had contemplated suicide as a child, the angst he felt in the wake of Terrell’s death was unlike any of his previous breakdowns. Combined with his failing marriage, growing financial problems and the Vietnam horror stories told by his younger brother Frankie, who had been drafted, Gaye entered a period of profound disillusionment. He was no longer interested in Motown as it was. He considered a career in the NFL, which was scuppered when the Detroit Lions refused to insure him against injury. It turned out his music career was still worth something, even if Gaye didn’t know it.

“What’s Going On” came at the right time. Renaldo Benson of Motown doo-wop quartet the Four Tops witnessed a violent police crackdown on anti-war protestors and scribbled some lyrics. Label songwriter Al Cleve- land added a catchy tune. Fearing Gordy’s wrath, the rest of the Four Tops wouldn’t touch it. Benson pleaded that it wasn’t a protest song but, rather, an idealistic love song for what could be. They didn’t buy it.

Gaye gave it a listen and added some lyrics of his own. Now a little dishevelled, bearded, drinking too much, thinking too much, Gaye connected with Benson’s idea in a way he never expected. It could be his “A Change Is Gonna Come”, Sam Cooke’s ode to the civil rights movement which transformed the late king of soul from folksy vocalist to indignant political commentator.

But the Four Tops were right. Gordy was having none of it. He reportedly called it “the worst piece of crap I ever heard”. Gordy particularly hated the experimental saxophone riffs, scatting and slurred bass sounds (which were not unlike the weed and whisky-fuelled recording sessions).

A couple of label executives disagreed and, behind Gordy’s back, released 100,000 copies. They sold. Another 100,000 sold quickly too. It became the fastest-selling single Motown had ever released.

Elated, Gordy offered Gaye the chance to turn “What’s Going On” into an album on his own terms, as long as it was done by the end of the month. No more assembly line. Gaye, Benson, the Funk Brothers, James Nyx Jr, David Van De Pitte, James Jamerson and more of Motown’s most skilled and stunted creative minds got to work. They went five days over schedule.

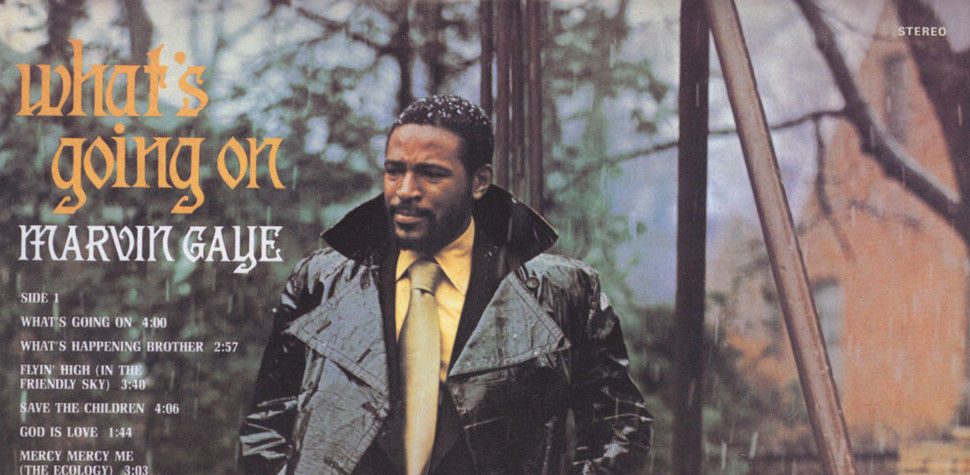

The What’s Going On LP sold two million copies and proved a commercial comeback for Gaye. The big-collar black coat he wore and gothic font which emblazoned the cover presented a different image for an austere new decade and an angst-ridden popstar. On the album, Gaye found not only his voice but, in those haunting double-track harmonies, another one too.

Each track deals with a different social issue. “What’s Happening Brother” was sung from the perspective of his veteran brother Frankie, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” verbalised Gaye’s fears about climate change, “Flyin’ High (In the Friendly Sky)” dealt with drug addiction, and album closer “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” placed America’s ghettos in a stark, relatable light. Just before the end of the album, the jazzy reprise from the title song returns and fades out. The echoes are still with us.

Unsurprisingly, the lyrics hold up today. Gaye laments “trigger happy policing” on one track and, on another, contemplates, “When will people start/ Getting together again”. The album’s clever conceit of posing its titular question as a meta reflection and a social ice-breaker is unforgettable. Especially now.

Gaye never had another album like What’s Going On. He never really got close. The interior sadness he explored with that re- cord’s spiritual dialogues found its home in a cocaine addiction by the mid-1970s. His personal life suffered, as did his music. Gaye would go through two separations by the end of the decade, worn out, facing a mountain of taxes. Distracted and unfocused, he ceded the ground of music as social analysis to Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield and more. A day before his 45th birthday, Gaye was shot and killed by his father in the Los Angeles house he had bought his parents after signing his first million-dollar contract, with the gun he had bought his father for Christmas. In a 2003 biography, Frankie Gaye alleged Marvin asked his father to do it.

The likeliest explanation for Gaye’s brief foray into politics, which enabled the resonating brilliance of What’s Going On, can be found in an unlikely place: his depression. In a 2018 Spectator column, former MP Matthew Parris observed that those who seek careers in politics tend to be the least well adjusted members of society. The same, he wrote, applies to its keenest observers. “People who are in trouble mentally, in their careers or in their relationships”, he wrote, “tend to develop strong opinions and feelings about the political scene with more intense interest than those whose lives are going well.” Parris concluded: “Those inhabited by emotional responses to problems in their own private lives will find in politics unlimited opportunities to harness their anger and their sorrow.”

Gaye’s masterpiece came at a time in his life when anger and sorrow abounded, and control seemed distant. It is a masterwork of funk-influenced rhythm and blues to which the musical credit, in truth, belongs to the set of innovative musicians and songwriters who found their ailing preacher at exactly the right time. But What’s Going On is also im- bued with the anguish of Gaye’s early thirties and a desire to throw the table upside down.

True to the spiritual chaos of the album, What’s Going On was the result of a confluence, not preordination. Motown legend Smokey Robinson would later recall visiting Gaye during the sessions: “I went to see him recording and he said, “Man, I’m not writing this. God is writing this.” And when I listened to it, I believed him.”