Morten Morland didn’t know what he was getting himself into. A Norway-born graphic design student with a vague interest in the strange British tradition of political cartoons, he interviewed The Times’ legendary cartoonist Peter Brookes as part of his research for a dissertation, bringing some of his own drawings as a discussion prompt. An assistant next door, impressed by the artworks, asked if he would cover some shifts while Brookes was away. Seventeen years later, Morland still draws for the paper.

Morland is perhaps best known for trialling animation in his cartoons for The Times, the first to do so on this side of the Atlantic. “I was fascinated by how little British cartooning had changed over the years,” he told The Mace. “We were still using the same tools as our predecessors, whereas everyone else in the newsroom had gone digital.” Inspired by Wall Street Journal cartoonist Mark Fiore, Morland began to create his own moving-image political cartoons. “It seemed to me at the time the natural progression, so I set out to learn it.”

Of course, it isn’t quite as easy as Morland makes it sound. For a two-minute-long animation at 24 frames per second (the norm even for hand-drawn animation), 2,880 individual frames are required. “I’ve got a fairly streamlined operation going now, but it still takes me two long days of intense writing, recording, drawing, animating and editing to produce what I do for The Times.”

And Morland’s intuitive modernisation of an art form that goes back to the late 18th century (later popularised by Punch magazine, launched in 1841), isn’t exactly the industry standard. Steve Bell, who has been a resident cartoonist for The Guardian since 1981 and the paper’s satirist-in-chief since the mid-1990s, has never changed how he approaches the work. “I’ve been doing this so long and seen so many ridiculous characters come and go, you eventually learn to approach it the same way,” he tells me.

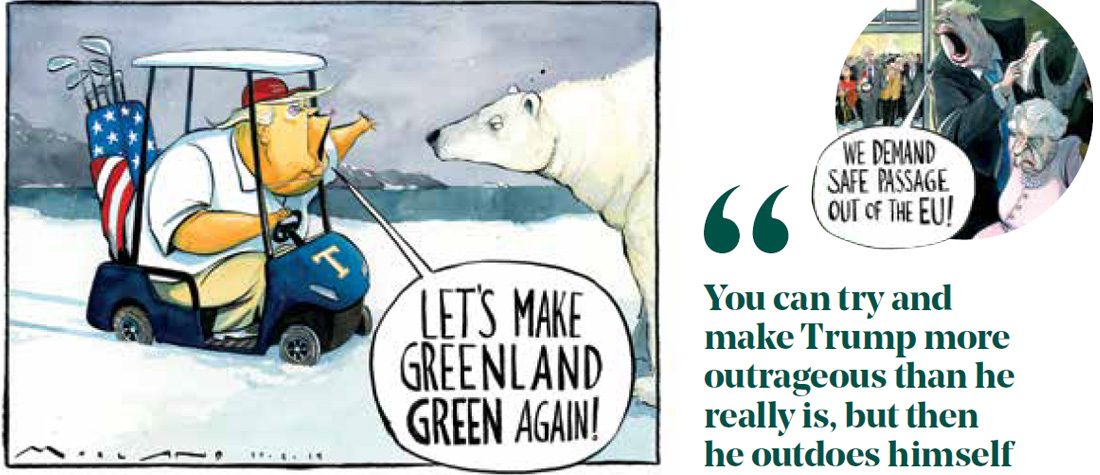

The obvious question to ask a cartoonist is how they’re able to respond to the absurdity of today’s political elites, never mind with coherence. Bell is one of several artists to admit that self-satirising politicians such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson are harder to portray in caricature, not easier. “You can try and make Trump more outrageous than he really is, but then he outdoes himself the next day,” he says. Appearing at the Cheltenham Literature Festival as part of his book tour, The Sunday Times cartoonist Gerald Scarfe called Johnson “a walking cartoon”. (Scarfe intended to speak to The Mace for this article but fell ill shortly beforehand.)

Part of the reason political cartoons have increasingly been considered outmoded is because of changing tastes among editors – and fears that caricature too often borders on racism. Bell has had difficulties dealing with one politician in particular: Benjamin Netanyahu. In June 2018, his drawing of Netanyahu and Theresa May looking on while slain Palestinian nurse Razan al-Najjar burned in the Downing Street fireplace was pulled by The Guardian amid accusations of anti-Semitism. Some felt Bell’s depiction of al-Najjar being burned alive was a reference to the Holocaust, a contention he remains frustrated by. “That was a wilful misreading,” he says. “It’s not an oven, it’s a fireplace!” Bell argues that “overcautiousness” has set in among editorial staff who formerly allowed cartoonists a much greater degree of license in what they were willing to publish. “If a cartoon is provoking a storm of intense nonsense from Twitter, that provides new challenges to editors and cartoonists.”

Would Bell draw Netanyahu again? “Of course I would. I don’t draw Netanyahu in that way to cause offence for offence’s sake. I draw Netanyahu in that way because he’s a bastard. You have to choose your targets. And a cartoon has to disturb, whether that’s through laughter or shock.”

Bell’s argument in favour of freedom of expression, especially among some of newspapers’ most outspoken holders of the pen, is persuasive. But the UK media, and the class of political cartoonists at the country’s major newspapers, is lacking the diversity that validates such discussions.

Hannah Robinson, a University of Edinburgh student and cartoonist for The Mace with a popular Instagram profile and online shop, thinks this problem has a simple cause. “I think part of the issue is that we tend to assume that white men are funny, or at least funnier,” she told me. “There’s this culture in comedy where we feel male comics are punching upwards and women are punching down, and have to be self-deprecating in order to be funny. That’s infiltrated cartoons, for sure.

“Matt at The Telegraph is a bit of an icon in the industry; he’s been doing it since the 1970s. But that was at a time when women weren’t seen to be serious options to take on roles like that, which is surely relevant.”

If Steve Bell is a household name for the cartoon as we know it and Morten Morland an ingenious pioneer in bringing new technology to the table, Robinson points to the cartoon’s next creative step. “Cartoons have always been observational for me,” she says, “a way of making sense of it all and bringing politics down to the ordinary level.”

One notable work of hers, titled “The BreXXXit Predicament”, features a couple in bed having sex and the man exclaiming: “Here we go… yes… wait, no, hold on, okay, I’m about to…” You get the point – it’s very funny.

Robinson believes the political cartoon is still a place artists and commentators alike can go to relieve themselves of the seriousness of the rest of the paper as well as offering a home for humour that doesn’t depend on giving offence.

“Being scandalous and making a point are some of the things that make political cartoons what they are,” she says. “We do live in a sensitive environment where it’s not always clear what you can say. But some of the cartoons coming out now, from Matt to The New Yorker, are still making some really interesting points without giving offence.

“Humour has changed and cartoons can still be absolutely brilliant. There’s an evolution going on, and not a bad one.”