The Reverend Richard Coles is a national treasure. He jokes about it in the best self-deprecatory English manner and he knows that, like every other treasure, he has cracks and flaws. In his equally well-written two previous books of autobiography, he showed himself warts and all. And in that sense this book is no different. He is as gorgeous and infuriating as ever.

He is painting on a much smaller canvas this time. This is the story of the short period in his life framed by the day his life partner, the Reverend David Coles, was taken into Kettering General Hospital, 13 December 2019, and the day of David’s funeral in Finedon on 3 January 2020. As the title suggests, it’s about Richard’s grief, but because the canvas is so small you get engrossed by the minutiae. Small practicalities take on a bigger significance. Hospital niceties. What to do with the five dogs. The “sadmin” of registering the death. The Anglo-Catholic rituals of a funeral pall “in midnight blue and purple… like a king-size bedspread on a child’s single bed”. Deliveries of chicken soup. David’s coffin attire of white cassock-alb, underpants and sequined stole – and the importance of his coffin facing priest-wise, the “wrong” way round in church.

Some moments made my eyebrows twitch. What with dinners with the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch and Christmas at Althorp with the Earl and Countess Spencer, it is a somewhat other-worldly existence. I thought my Twitter addiction was bad, but I was fascinated by how important social media is for Richard, as a source of news, a means of announcing David’s death and a place of comfort. Less “I look to the hills whence cometh my succour” than I look to my 225,000 followers who give “99.99999% loveliness”. What was less surprising, sadly, was the appalling homophobic abuse he suffers. One anonymous letter read, “Dear Mr Coles, I can’t begin to tell you how happy I am to hear of the death of your partner.”

Here’s my gripe, and it maybe says more about me than about Richard. I hadn’t expected a eulogy, but I had hoped to get to know David better. Properly memorialising the departed is a vital part of the process of grief. But the few glimpses of David Richard allows us come as if through a glass darkly, and he remains an indistinct figure, a ghost, an absent presence. Richard hints at unhappiness, harsh words and threats of separation, but things seem too raw for openness.

Let me explain. Richard and I are very similar. We’re both 59 and gay. His songs with the Communards were the soundtrack of my coming out. We have both changed career, in different directions. I was a priest in the Church of England in Northamptonshire and I’ve worked for the BBC. Now I’m an MP. I’m fond of him.

We have one other thing in common – alcohol has wreaked havoc in both our families. Richard’s David was alcoholic – “an alcoholic” if you accept that dependence on alcohol can change your very nature or just “alcoholic” if you see dependency as an illness that doesn’t define the person.

In my case it was my mother, a beautiful, talented graduate of Glasgow School of Art. It was my thirteenth birthday and we had recently moved back from Spain to a house in Eldorado Crescent in Cheltenham when Mum came and sat on my bed and first told me she was drinking too much. I don’t think I knew what she meant then, but it felt like the last moment of honesty between us. For the next 15 years she drank between one and two bottles of vodka a day. (Vodka because it didn’t tell on her breath.)

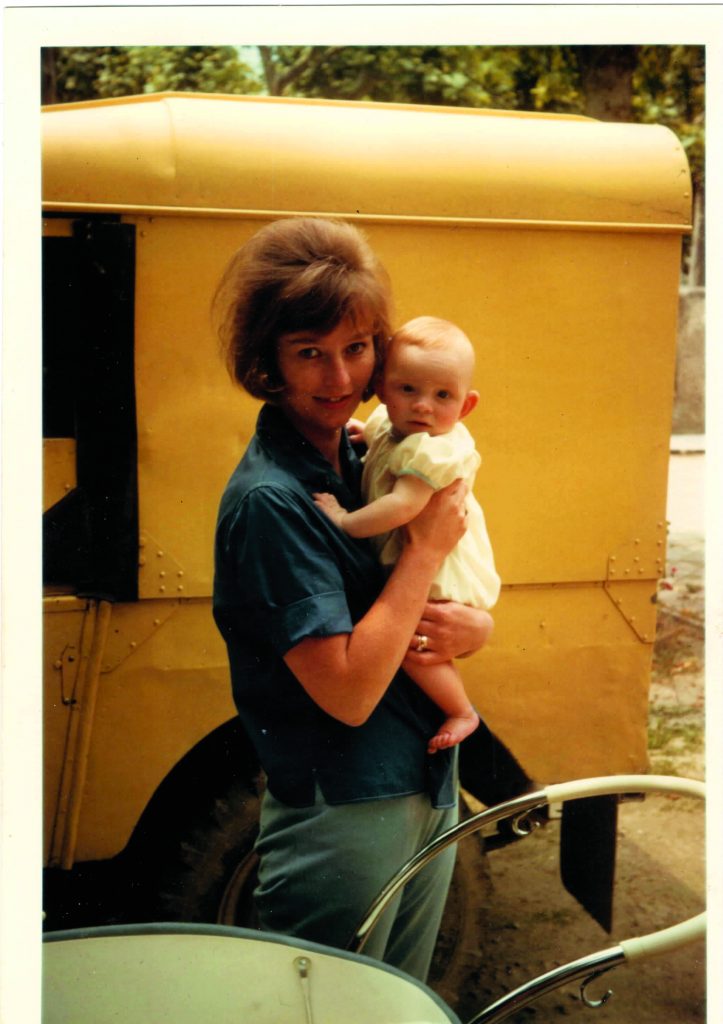

Anne Bryant with baby Chris

She was ashamed, of course. She hated admitting she was drunk. So she hid the bottles and denied it till she was blue in the face. If I found her stash, I would pour it down the drain while she complained about the waste. Once I found 126 empty bottles in the loft. This was long before recycling.

Stopping was never easy for her. I don’t know how many times I had to take her through withdrawal, with shakes and terrible fits. At one point she felt unable to leave the bed for months on end. She was in and out of hospital. Things got no better when my parents divorced. She lost her home and moved to a caravan park.

I had hundreds of rows and shouting matches. With her friends who turned up with bottles of booze when she was trying to stay sober. With men who took advantage of her. With fellow pupils who laughed at her when she turned up drunk at school events. With the off-licence that let her have booze on tick and run up a credit bill she could never afford. And above all with her, because every lie cut deep. I selfishly said things to her I wish I’d never said.

There were funny moments. She would be getting steadily more sloshed in the kitchen, but we could never find her drink. Nor could we understand why the avocado stone we had suspended with toothpicks over a glass of water (like every middle-class family in the street) never put down roots. And then we worked it out – it was vodka, not water. On another occasion I came up with the bright idea that a liver function test might shock her into quitting. It backfired. Her liver was apparently fighting fit. She laughed.

Towards the end I found her a place in Glasgow and she was drawing again. When I visited, I took her shopping at M&S for clothes. When I came back two weeks later, she’d exchanged them for vodka. We rowed.

I admit I had hoped that Richard’s book would explore the hell of living with someone you love who is in thrall to booze. It’s unfair of me. But I hope he writes that book one day.

If you’re worried about your own or someone else’s drinking, call the national alcohol helpline on 0300 123 1110