During the first referendum on Europe in 1975, those campaigning to leave likened the Treaty of Accession to Chamberlain’s Munich Agreement and appeasement. The year before, as he was preparing to address the Labour Party conference, the West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt asked his cabinet what he might say in his speech that would help convince voters to stay in the EEC. One of his ministers, who had just met her British counterpart, Barbara Castle, told him: “The only way to keep Britain in the European Community is not to remind it that it is already in.”

This memo formed part of an exhibition at the German House of History in Bonn in 2019 entitled “Very British: A German Point of View”. This was one of the museum’s most popular shows. It had been devised before the referendum, but its contents were amended to include a room focused on Brexit. Hoffman admitted Germans’ fixation with Britain’s travails had boosted visitor numbers.

Germans have devoured British subculture, pop music, TV shows (they too found Fawlty Towers funny in a self-deprecating way), the glamour of Emma Peel and the Avengers. Many can recount holidays to Cornwall, Scotland and the Lake District in their camper vans. They are glued to Premier League football. They obsess about the royal family (Germans, from Hanover, they like to note). They love English traditions, even when they make them up. Every New Year’s Eve, the entire country, young and old, watches Dinner for One. First aired in 1963, it is the most repeated TV programme in history, the 90th-birthday dinner of Miss Sophie, a bejewelled English aristocrat. Germans know every line. No Briton I have met has ever heard of it.

The show is funny, informative – and painful. It is about an unrequited love.

That love has faded fast since 2016.

Britain, on the other hand, never seems to know what it wants of Germany. When its economy struggles, as it did in the mid-1980s and mid-’90s, it is derided as the “sick man of Europe”, over-regulated and hidebound. When Deutschland AG corners global markets, it is over-weaning and rapacious. The British don’t want Germany to throw its weight around the world, yet they do want it to pull its weight.

And all that, before the “battle” of the vaccines. The many failures of the European Commission have pained Germans. Some wondered why they bothered handing jurisdiction to Brussels in the first place. Early on in the pandemic, in a group with the French, Italians and Dutch, they were making good headway with the pharmaceutical companies. They were furious with the Commission and its (German) president, Ursula von der Leyen. After all, the successful trial the previous November of the first vaccine, Pfizer- BioNTech, had been heralded as a very German success story.

The Commission’s efforts to offset blame were bad enough. Its panicked attempt to interfere with the newly-erected Irish protocol caused considerable, perhaps irreparable, damage.

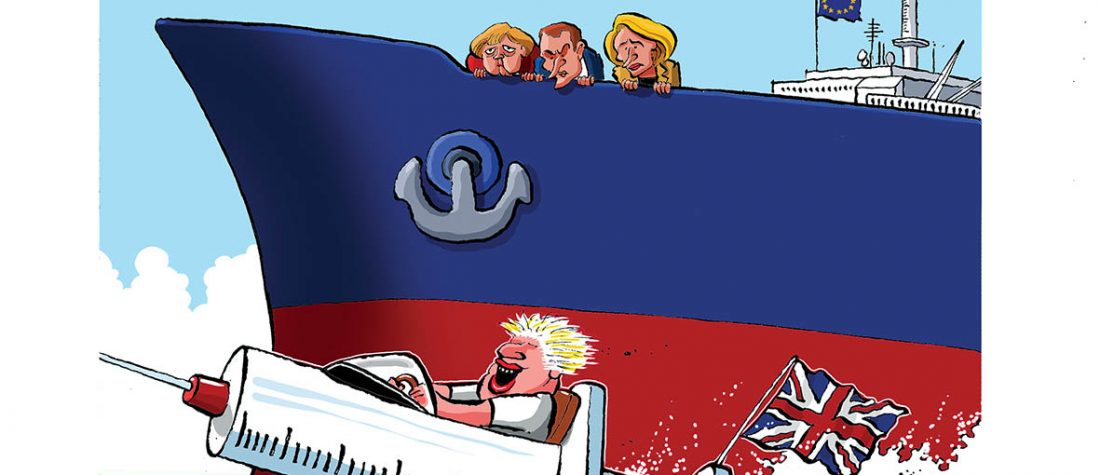

Immediately, the DUP went on the rampage, seeking legal advice on removing the protocol. Many Brits enjoyed watching Von der Leyen’s hapless attempts to explain the bureaucratic sludge. They relished her description of the UK as the speedboat and the EU as the tanker.

The worse it has got, the more Germans have indulged in their favourite pastime – self-criticism, thinking the worst of themselves.

Locked down, like pretty much everyone else in Europe, Germans had already begun the year with trepidation. Towards the end of 2020, the relative consensus on dealing with the pandemic began to fray. Covid-deniers and anti-vaxxers mounted vocal, if small, demonstrations. The government responded with less precision than earlier in the crisis. Some of the regions became more fractious. Rules were not adhered to as strongly as they should have been.

Britain, alongside Israel and even the US, has been faster and nimbler on the vaccine. Even the most ardent Johnson critic is required to concede that. This was the first instance of the Johnson government doing anything right during the pandemic. Much of the British media went into instant schadenfreude, and “told you so” mode over Brexit. Who needs solidarity when you can be nimble? Might Johnson emerge the “victor”, some wondered? Might he “get away with” whatever criticisms a public inquiry on the pandemic might throw at him. After all, hadn’t his team scored the winning goal in the final minute of the game?

Politics reduced to sport or a game. A very British way of looking at things.

People were encouraged to forget that, throughout 2020, Britain’s response to the pandemic was a study in failure. Every development was hailed by Boris Johnson as “world beating”, only to fall apart. The contrast with Germany’s relative success in the early stages made it all the more painful for Brits who are often frightened to look at their own country through a clear lens.

Announcing 100,000 deaths in Britain, Johnson said it was “hard to compute the sorrow contained in that grim statistic”. His head hung low, he could not answer a question why Britain’s death toll was so much higher than any equivalent country an d twice as high as Germany’s. It was a rare and unconvincing display of humility. It didn’t last long.

Even though the death toll has tailed off sharply, another grim milestone, 150,000, was reached in the final days of March.

Germans know that Johnson and his ministers have presided over the highest per capita death rate in the world and one of the worst GDP falls among wealthy nations. They don’t brag at the contrast. That is because they are too busy indulging in their default emotion of anxiety.

Even after the pandemic, will Britain, I wonder, ever be big enough to learn from others? As the Germans at least try to do. Bragging about a single success neither wins friends or influence people.

Yet, in spite of everything, a concerted attempt is being made in both countries’ foreign offices to rediscover what Germany and Britain have in common. The answer is a considerable amount.

Some of the shared agenda lies in foreign policy. This is the area where the Germans miss the Brits most in Brussels. Already the EU is appearing less cohesive and less courageous when it comes to taking on China and Russia. Germany and France may have always been the pivot, but the two capitals struggle to see eye to eye.

In business as in culture, Britain and Germany have ties that bind. Both countries had (at least before free movement ended) a healthy exchange of talented young people working in engineering, tech, science and the creative industries. The decentralised Germans are particularly keen to push collaborations involving their own 16 Länder and the nations and regions of the UK.

As the UK hurtled into an uncertain future with the flimsiest of Brexit deals, as trade suffered, goods became scarcer and costlier, as the health service suffered from the exodus of European workers, Johnson and his ministers rallied behind the flag. Even though ministers spoke of a fresh “special relationship” with the EU, their first instinct was to pick fights with these supposed new friends.

Asked in an interview why the British had early access to the Covid-19 vaccines, (a few weeks earlier than France, Belgium, America and other countries), the education secretary, Gavin Williamson, came up with an ingenious response. Rather than saying that regulators had pushed approval through more quickly, he asserted: “That doesn’t surprise me at all because we’re a much better country than every single one of them, aren’t we?”

The response of Germans when they read that: a shrug of the shoulder.

Encouraging closer ties is an important endeavour, which I’m helping on behind the scenes. Expectations, though, need to be managed. For Germany, what matters most is the future of the EU.

A bigger problem nags away. It is about the style and tone of government. The pandemic has said much about the organisation of society and the capacity of the state. Invariably, Angela Merkel has been cited as an exemplar, alongside Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand, the leaders of Taiwan, Finland and elsewhere. The fact that they all were women may well have played a part. People have their own views on that. But what matters far more in Merkel’s case is her science background and her character. Germans do not like cutting corners. She believes in facts not grandiloquence.

At a British-German dinner I attended in Berlin in 2019, the justice minister at the time (and now MEP), Katarina Barley, gave this painful prediction: “Even if we agree with you in the future, we will always be more distant, because family comes first, and you are no longer family.” She should know, being half-British. Her father’s side comes from Brexit-supporting Lincolnshire.