I am passionate about history and, above all, the way it is taught. When I did GCSE history many years ago, we studied Adolf Hitler’s Germany, crime and punishment, which was mainly about Jack the Ripper, and the Arab-Israeli conflict. That was it. I then did my A-levels, when we did the Tudors and the civil war—Oliver Cromwell, Charles I and all that. Our curriculum is just far too narrow. It is easy for the Government to point to the option of teaching topic 3—“Ideas, political power, industry and empire: Britain, 1745 to 1901”—at key stage 3. However, it is not mandatory; it is only one of many topics that can be chosen by schools and teachers. It is clear that the signatories to the petition do not feel that this is enough, and I must agree with them.

The Committee found that 45% of primary school teachers and 64% of secondary school teachers who responded to our survey disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that:

“The National Curriculum ensures that students in my school experience a balanced range of ethnically and culturally diverse role models.”

Our inquiry has also shown that, far too often, subjects are not being taught because teachers lack confidence and, above all, proper training. One in four teachers told us that they lack confidence and the ability to develop their pupils’ understanding of black history and cultural diversity, with 86% calling for specialised in-school training to help address this. It is leaving students unprepared when they reach degree level, which continues a cycle of a lack of confidence within the subject.

Dr Deana Heath, who teaches southern Asian and imperial colonial history at the University of Liverpool, said: “I face an uphill struggle at the start of each new academic year. Many of the undergraduates who greet me know virtually nothing about any of the subjects I teach.” Although some black and BAME history is now taught in schools, it is far too narrow in scope. Most students’ experience of racial history up until A-level is incredibly American-centric. Students learn about American slavery and the black civil rights movement. Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and even my great hero, Muhammed Ali, are now studied at GCSE by many pupils. However, very little black British history is taught.

When students learn about the transatlantic slave trade, Britain’s role is often simplified or is just a small part of their study. Few secondary school students learn about British slave plantations or slave ships. Even fewer learn how British involvement in the global slave trade shaped domestic economics, politics, empire building and industrialisation. Black British history has largely been forgotten in the UK curriculum, even though there have been black Britons since Roman times.

A student might have a chance to learn about the Montgomery bus boycotts in Alabama, but often does not learn about the history of bus boycotts much closer to home. In Bristol in 1963, there was a successful bus boycott for the Bristol Omnibus Company’s refusal to hire black or Asian bus crews. Many in the UK will know the name Rosa Parks, but not enough know the name Paul Stephenson. On the same day in 1963 that Martin Luther King gave his iconic “I have a dream” speech from the steps of Washington, the British Omnibus Company announced that there would be no more discrimination in the employment of bus crews.

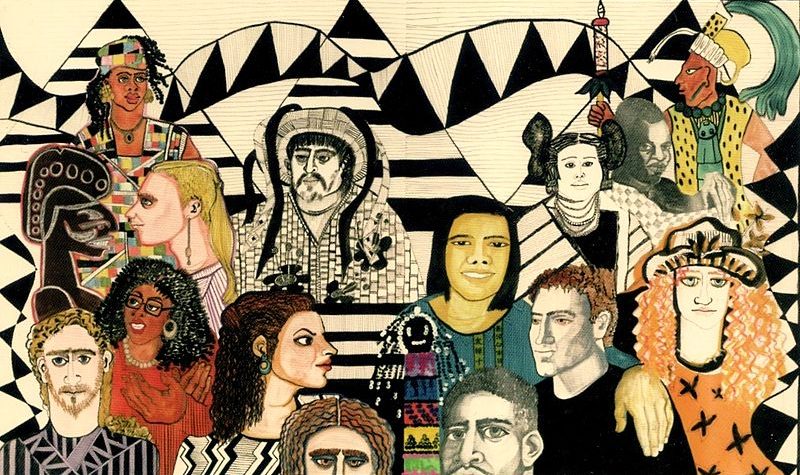

I suspect we feel more comfortable looking at discrimination perpetuated by America than we do taking a closer look at our own history. We cannot continue to whitewash the UK’s past. Students must be taught a nuanced and honest view of British history. British and European history studied at GCSE and A-level all too often seems to be the history of white powerful men. History curriculums, especially until university, are too frequently studies of monarchs, politicians and military leaders. That creates an often Eurocentric white male, upper or middle class view of history and knowledge. That is not a full history of Britain, Europe or the world.

The roles of working classes, minorities, women and all those who have been underrepresented have not been granted the historical significance they deserve. Not only is teaching such a narrow view of history a disservice to the subject; it makes it far less accessible. Students in British secondary schools often feel too far removed from the Churchills, Napoleons or Henry VIIIs. A diverse curriculum is necessary to write new entry points in history—a new standpoint from which we can understand our past and the world we currently live in.

The few women featured in the curriculum are either painted as exceptions to their sex, such as Florence Nightingale, radical, such as the suffragettes, or are monarchs such as Elizabeth I and Victoria. Very few non-white women are mentioned in history textbooks for secondary school students. Mary Seacole is one of the other very few. Studies of women such as Seacole must be encouraged, to recognise the diversity of Britain’s past and the importance of such diversity, but unfortunately that has taken too long.

William Howard Russell, a war correspondent for The Times, wrote in 1857 that he hoped England would not forget Seacole as:

“one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them, and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead.”

Yet it seems that exactly that happened for many years. In 2016, a statue of Seacole was erected across the road from this place. When the lockdown measures are lifted, I urge everybody to go over and see the wonderful statue to that wonderful woman. It took 12 years to raise the funds required and should be a symbol of pride in a black British heroine. Unfortunately, even the little act of posting a photograph of me with the statue on Twitter resulted in some terrible abuse about the role of Mary Seacole. That has no place in society. It amazes me that somebody who did so much for the people she looked after would be questioned about whether she was a nurse. That has to stop. Mary Seacole should be celebrated as an influential figure in British history. Her story, and the racism she faced, ought to be taught widely in history curriculums. We also must make sure that she does not stand alone. The history of Britain is incredibly diverse, and the curriculum should reflect that. It is not enough to pick one figure from history. The diversity of Britain and the way that attitudes to and experiences of race, sex, sexuality, disability or class have shaped history are vital to our understanding of today.

Ultimately, it all matters because of the impact it has on young people. A report from Paul Campbell, a lecturer in sociology at the University of Leicester, found:

“The lack of a sufficiently diverse or decolonised curriculum and faculty meant it was often difficult for black students to be able to connect content and assessments directly to their own lived realities”.

He found the students were multiply disadvantaged and “have to work harder than their peers to connect with assessment and curriculum content.”

The lack of diversity in our curriculum can be found throughout our education system; although the petition is focused on history, it is equally true of the likes of English literature and other subjects. The Black Curriculum, one of the leading charities in this field, says that its aim is to provide a sense of belonging and identity to young people across the UK. To me, that is the whole point of the debate. It is our duty to get this right so that all students see themselves represented in education.