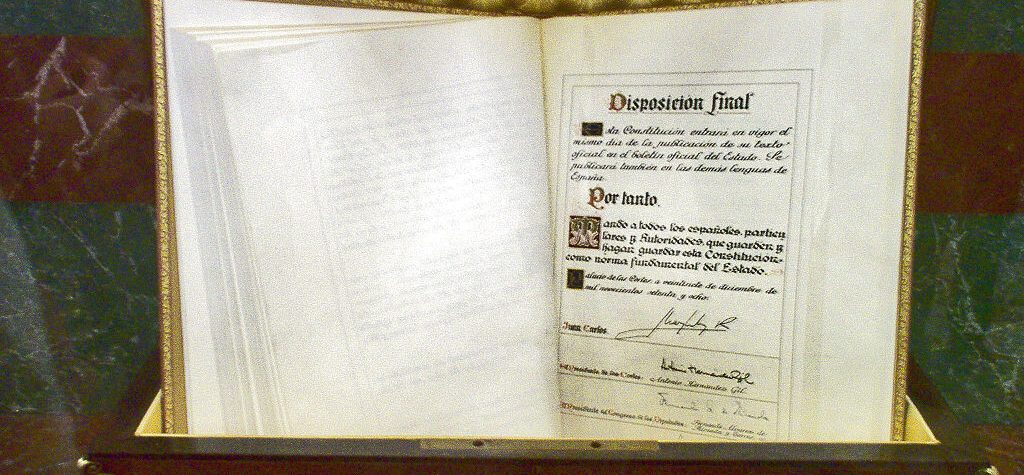

For four years now, Spain has been undergoing a stealthy form of regime change. Since taking office in June 2018 on a coalition with the far-left Podemos and a constellation of left-regionalist parties, the government of socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has sought to replace what Spaniards call their “regime of 1978” with a totally new dispensation. That regime took shape in the years following Franco’s death in 1975, as parties theretofore banned under the strongman’s 40-year rule agreed with pro-modernizing elements across the aisle on the country’s new democratic Constitution. That Constitution was soon after backed by over 90% of the voting public in a referendum and is still polling to this day, despite some less popular facets, at around 70% of approval among Spaniards.

As a crucial condition of that transition, the previous year had seen the country’s best effort to bury the last remnant of the three-year Civil War that Franco’s nationalist camp had claimed power by winning in 1939. By at once pardoning seditious acts against Franco’s regime and expunging that regime’s crimes against opponents, the amnesty bill passed in 1977 was a way to decisively—and definitively, we thought—turn the page on a half-century of us-versus-them, internecine animus. Along with Spain’s modern welfare state and its quasi-federal territorial arrangement, this form of wilful amnesia—of both sides resolving to leave the 1936-1939 conflict and the ensuing 40 years in the dustbin of History—has proved the bedrock of the country’s democratic experiment. It is now being undermined wholesale from on high.

The 1977 amnesty is on the chopping block of a new bill the Sánchez government introduced a year ago that cleared a first legislative hurdle on Tuesday and is expected to make it out of committee on July 14th. The bill leaves the 1977 amnesty technically—but not substantially—in place, although one of the government’s coalition allies, the left-Catalan Esquerra, lobbied (unsuccessfully) to scrap it altogether. It is perhaps best understood as building on a previous bill made law in 2007 under the preceding socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2005-20011) but largely nullified in the centre-right interregnum of Mariano Rajoy (2011-2018). Rajoy neutered the bill by appropriating no money for its projects but is coming under fire from the right-wing Vox party for falling short of scrapping it altogether.

That 2007 bill had acknowledged the victims of Franco’s 1936 coup and his ensuing 40-year regime but refrained from invoking the “crimes against humanity” category. It also left the task of exhuming an estimated 114.000 missing bodies of said victims to families and non-profits. The new bill ups the ante in several major ways. It refers in glorious terms to all anti-Franco acts, however violent. It leaves the door open for the strongman’s alleged crimes to be trialled internationally under the UN’s 1968 Convention, thus undoing their 1977 expungement. The bill would also create an “Office of Victims” to tally up Francoism’s human toll, something most historians consider futile. It would aid exhumation efforts through a public repository of DNA data and introduce “democratic memory” courses in school curricula.

But perhaps the bill’s most controversial aspect is its zeal to right the “violation of rights” committed during two periods. The first (1936-1978) was already the subject of Zapatero’s 2007 bill, and will this time be examined by a so-called Council of Democratic Memory. But the rights allegedly violated stretch into a second period (1978-1983) that goes right up to the first year in office of former Prime Minister Felipe González, who was himself… a socialist! This particular rider has been pushed by the far-left, pro-Basque independence Bildu party. Bildu’sleaders to this day refuse to condemn the ETA’s terrorism and hope to hereby draw attention to the counter-violence of the GAL, a paramilitary force from the early 80s that met the ETA’s fire with fire, and which they allege was in cahoots with González’s Interior Ministry.

The misalignment between what the bill claims to pursue, and its inescapable outcome couldn’t be clearer. “Democratic memory”, its preamble intones, “is a society’s duty to repay its debt towards the past”. Spain, the preamble goes on, has been eschewing its day of reckoning, unlike other West European nations forced to reckon with the horrors of World War II in the Holocaust’s wake. Except that Spain’s Civil War is seen by most Spaniards not as a fight of good versus evil, but rather as an internecine, pointless bloodbath that would be better left unstirred. The effect of this bill, therefore, will be to pointlessly pit Spaniards against one another whilst the government reaps what French historian Benjamin Stora calls “memorial rent-seeking”.

Jorge González-Gallarza (@JorgeGGallarza) is the executive director of the Madrid-based think-tank Fundación Civismo and the co-host of the Uncommon Decency podcast on Europe (@UnDecencyPod).