I was brought up to believe that Britain was different. Other countries were all terribly corrupt, but we were no banana republic, we were clean. The police, the civil service, the monarchy, they kept the country on the straight and narrow, so our politicians didn’t do dodgy deals or lie. Maybe that was a bit idealistic, yet I would bet my last rouble that if you asked most Tory MPs today about the incorruptibility of Britain, they would still hold that view.

But I’m not so sure. Corruption has taken many forms over the centuries. The Tudors and the Stuarts thought the “canker of corruption” included sexual immorality, licentiousness, adultery or any other form of sinfulness that demonstrated humanity’s fallen state. Yet they happily countenanced all but the most egregious examples of crown cronies abusing monopolies. The East India Company’s monopoly continued until 1833 and Samuel Pepys’s attitude towards taking gifts from Navy clients was that as long as he was taking them from everyone, he wasn’t showing favouritism. Ministers expected to farm their positions for their own benefit and it was still legal to sell government posts until 1809 and military commissions until 1871.

Perceptions have changed, but the central point remains. Modern corruption comes in many forms.

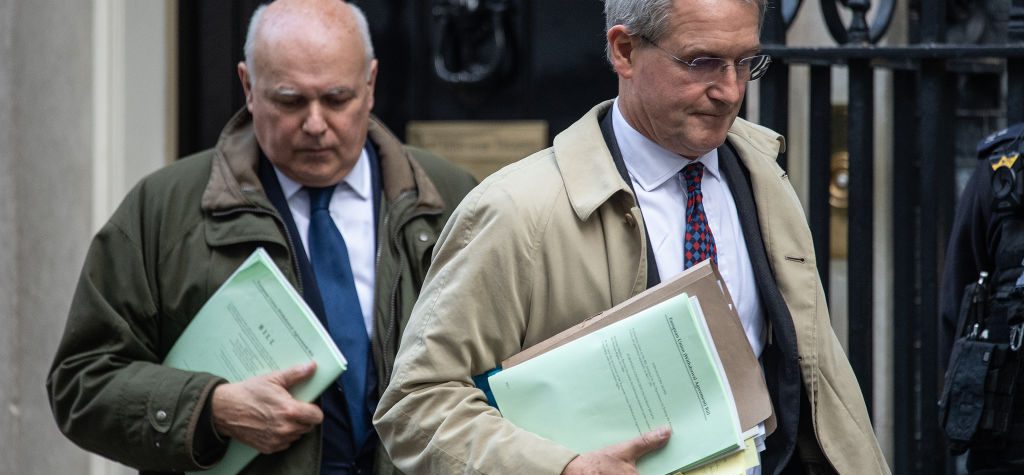

Top of the list comes the abrogation of power. This is endemic in Britain where we have few checks and balances and the motto is “winner takes it all”. As long as prime ministers maintain a majority in the Commons, they have total command. They alone appoint, dismiss or discipline ministers, dole out honours and seats in the Lords, determine if and when parliament sits, when it goes into recess or is prorogued and what legislation it considers, establish the machinery of government and determine all taxation and expenditure. A prime minister can use their majority to alter or suspend the standing orders of the Commons at will. In the last year, ministers have attempted to dismantle the Commons standards system to protect Owen Paterson, cut the powers of the Electoral Commission and seized back the power to decide the date of the general election according to the interests of the governing party.

Second is the abuse of ministers’ powers of discretion. Since Boris Johnson came to power we have seen a whole raft of new “funds”: the shared prosperity fund, the towns fund, the levelling up fund. What they have in common is a competition between different areas of the country and the requirement that MPs lobby ministers for their pet schemes. This is corrupting. Ministers want to help friends. Friends want to help ministers. In America this “pork barrel” politics is the bane of good governance.

Third is nepotism. Some actually applaud it. When Viscount Melbourne was home secretary and his deputy died, the Prime Minister Earl Grey recommended that his own son, Viscount Howick, take the post. Melbourne’s only objection was that he might be too squeamish about the death penalty. Similar favouritism is alive and well in UK politics. David Cameron seemed to ennoble virtually everyone who ever worked for him. Johnson put his younger brother in the Lords.

More mundane is the appointment of friends to arts organisations like the National Portrait Gallery, the National Gallery and the BBC. The government failed to get their man, Paul Dacre, in charge of Ofcom, largely because he knew nothing about broadcasting or other media. But it has become commonplace for ministers to insist on a new list of potential appointees which only includes Conservatives. The only criteria for appointment seem to be support for the PM, opposition to the “woke” agenda and a desire to engage in culture wars.

Fourth is common or garden hypocrisy. That’s when those in power lay down rules for everyone else, but fail to abide by them. What makes this especially toxic is when complaints are dismissed as “fluff”, as Jacob Rees-Mogg did recently. That is just an arrogant excuse for bad behaviour and it infects the powerful with a sense of entitlement.

Fifth is lying. I know everyone thinks politicians lie all the time, but an out-and-out lie is rare in politics. Historically it has always led to a resignation. But when you have a prime minister who was sacked twice for lying and repeatedly lies about everything from the trivial to the monumental, government by consent is endangered by epochal cynicism. Britain is getting more corrupt – and we need to stop the rot.