Nearly six years ago, I attended the first ever meeting of the Global Irish parliamentary diaspora, a gathering in Dublin of elected officials from national assemblies all around the world, each with Irish ancestry in common, and for most of us sharing the Catholic faith. My father was born in Dublin and as a child moved to England with his family in the 1950s. During this gathering, I was asked by Mark Daly, a member of the Irish Senate, whether I was related to the former revolutionary leader Michael Collins. I gave my usual answer that I was not aware of any direct connection. ‘Let me stop you right there,’ Mark replied with a laugh. ‘The correct answer is to say that you are distant cousins.’

Given that around one in ten citizens of the USA identify as Irish Americans, it’s not surprising that many Presidential candidates find that long lost link to Ireland. Even Barack Obama discovered a great-great-great-grandfather from Moneygall in County Offaly and quipped in a 2011 visit to Ireland that he’d ‘come home to find the apostrophe we lost somewhere along the way.’ However, for the Irish American Catholic Joe Biden, his ties to the old country are bound tighter. While he was not with us for that gathering in Dublin, he more than qualified through the direct links of his Irish American maternal grandparents, Ambrose Finnegan and Geraldine Blewitt. In 1850 Patrick Blewitt emigrated from Ballina in County Mayo, settling in Scranton Pennsylvania, the same town where Joe Biden would be born just over ninety years later.

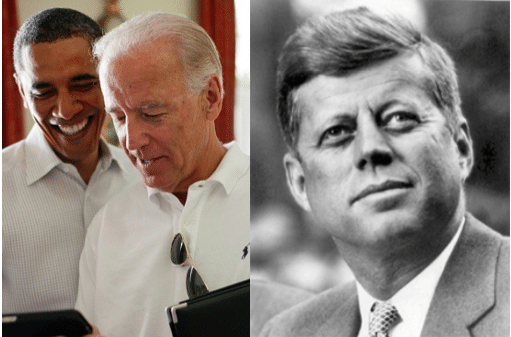

Through his Finnegan family tree, the President-elect is also a cousin of the Irish rugby international Rob Kearney. During the recent Presidential campaign, much was made of Biden’s remark, when the BBC reporter Nick Bryant asked him in passing if he had any words for their audience: ‘The BBC? I’m Irish,’ he said. However, we should not believe that he will look at the United Kingdom through a green filter, any more than did the last Irish American Catholic President, John F Kennedy.

John Kennedy remains the youngest man to be elected President, and Joe Biden the oldest. The Kennedys enjoyed a glamourous millionaire lifestyle, whereas the Bidens were a middle-class family who, like most Americans, had known times of struggle. Yet both men arrived at the Presidency with an international outlook in sharp contrast to the economic nationalism of Donald Trump; their politics shaped by personal experience, as well as their Catholic faith and Irish ancestry. As the son of the US Ambassador to London, Kennedy had travelled extensively in Europe and served in the Pacific during World War Two. Joe Biden is one of the most experienced American politicians to be elected to the White House as a former Vice President, and Chair of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Family tragedies define both men and, for each, the influence of Catholic social teaching would seem to have shaped their convictions of the moral necessity to fight oppression and bring people together. Kennedy often referenced the Bible to support these endeavours, stating in his inaugural address in January 1961, that we should ‘heed in all corners of the earth the command of Isaiah – to “undo the heavy burdens…and to let the oppressed go free.”’ Similarly, in his acceptance speech following his election victory last November, Joe Biden exhorted that, ‘The Bible tells us that to everything there is a season — a time to build, a time to reap, a time to sow. And a time to heal. This is the time to heal in America.”

For both men, their interpretation of the struggle of the Irish people is woven into the story of the American revolution and the cause of liberty around the world. Their call has been for all freedom-loving peoples around the world to play their part in that struggle, which is of far greater significance than differences over matters of domestic policy. JFK drew on this in his inaugural address, with his call: ‘to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, “rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation.”’

The day after the 2016 Brexit referendum, Vice President Biden gave a speech at Dublin Castle as part of an official visit to Ireland. ‘As longstanding friends of the United Kingdom, the United States respects their decision’ he said, adding that ‘as the leadership in London and Brussels determines what this new relationship will look like, we will continue to work with our partners to navigate a new road ahead while continuing to promote stability, security and prosperity around the world.’ These will be the challenges of the 2020s, made harder and more uncertain by the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. The Special Relationship between the UK and the USA has often been at its best when strengthened by a sense of shared mission. That is as strong now as it was during the administration of the first Irish Catholic President. In the words of Seamus Heaney, quoted by Joe Biden during his campaign, as they were by President Bill Clinton at the time of the signing of the Good Friday agreement: ‘This is our moment to make hope and history rhyme.’

Damian Collins is MP for Folkestone and Hythe

This piece originally featured on the Catholic Herald website catholicherald.co.uk